A Brush with Capt Cook and George IIIs Navy

Ship Cove: Queen Charlotte Sound 2015

I recently had to opportunity to visit Ship Cove in New Zealand's Queen Charlotte Sound for the second time.

As per my previous visit I was with a group of 40-odd 11 and 12 year old children on a school trip. A lightning visit is was too. Consisted mostly of a quick lunch, after which I led a half-an-hour tramp (hike for non-Kiwis) up to a waterfall in the stream that Capt Cook watered his vessels from. A brief brush with history, you could say.

On the way there and back a bief look around the memorial, attend to a sprained ankle, and then off fishing...

First details of the Memorial, as story in itself:

British explorer James Cook first brought his vessel, the Endeavour, into this bay in the Marlborough Sounds, in January 1770. Cook himself named the bay Ship Cove and returned to it on four subsequent occasions in 1773, 1774 and 1777, mostly to rest his crews and refurbish and provision his ships.

Captain James Cook spent a total of 328 days exploring the New Zealand coastline during his three voyages. The initial purpose of Cook's voyages was to observe the Transit of Venus in Tahiti and then search for a great southern continent which was believed to exist - Terra Australis. Cook was to return to Ship Cove in Queen Charlotte Sound, on five separate occasions. He spent over 100 days there, as it provided safe anchorage, food and fresh water and timber for repairs to his ship. 1

Cook's First Voyage involved a six month long circumnavigation of Aotearoa/New Zealand. His ship, the Endeavour, sailed into Ship Cove, on 16 January, 1770. He described it as a "very snug cove" and recorded that: "The number of Inhabitants hardly exceeds 3 or 400 people, they leive (sic) dispers'd along the Shores in search of their daly (sic) bread, which is fish and firn (sic) roots for they cultivate no part of the lands". (Journals of Captain Cook, 6 February, 1770)

Cook's Second Voyage involved two ships, the Resolution, commanded by Cook, and the Adventure commanded by Lieutenant Tobias Furneaux. They left from Plymouth in England on 13 July 1772 and met at Ship Cove in May 1773, but lost contact with each other after they left Queen Charlotte Sound and later both visited the Marlborough Sounds area separately.

Cook later learned that ten men from the Adventure had been attacked and killed at Wharehunga Bay, Arapawa Island. While it was expected that Cook would seek revenge for the killings on his return (third) voyage, he did not, and acted with commonsense and restraint.

Attempts were made by the Europeans to introduce various animals. Furneaux liberated a boar, and a sow and a pair of goats were released on Arapawa Island. Rats, chickens and more pigs were also introduced to New Zealand by Cook's ships. Cook put a ewe and a ram ashore at Ship Cove and was disappointed with his failure to introduce sheep: "Last Night the Ewe and Ram I had with so much care and trouble brought to this place, died, we did suppose that they were poisoned by eating of some poisonous plant, thus all my fine hopes of stocking this Country with a breed of Sheep were blasted in a moment." (Journals of Captain Cook, 23 May 1773)

The Europeans left potatoes, and turnips as well as other vegetables. They also brought serious diseases to Maori, including tuberculosis, and venereal diseases.

During this Second Voyage, Cook recorded that some Maori families were living near their ships and supplying them with fish. He acknowledged that their fishing methods and expertise were superior to those of his own countrymen. Cook left the Marlborough Sounds on 7 June 1773, but he returned to Ship Cove again in November, leaving on 25th November, to return in October 1774, still on his Second Voyage.5

Cook's Third Voyage commanding the Resolution and accompanied by the Discovery, included a stay at Ship Cove "in our old station" in February 1777 to refresh and refit the ships. Captain Cook was 47 years old and clearly weary with the demanding and dangerous voyages and dealing with the various peoples of the Pacific. He began to behave less tolerantly and on 14th February 1779, over-reacted to a theft in Hawaii, which resulted in a fight in which Cook was killed.

During his three voyages to New Zealand, James Cook mapped the outline of the country with considerable accuracy. His observations of Maori culture, and natural history, combined with the observations recorded by his men provide a rich source of information and his comments on the abundance of whales, seals, timber, and flax encouraged British interest.

At the instigation of Robert McNab, minister of lands and a historian of late 18th and early 19th-century New Zealand, this monument commemorating Cook’s association with Ship Cove was erected, and inaugurated by the Governor, Lord Liverpool, on 11 February 1913.

Not a great deal of time to explore the historical aspects, but I took a moment to pause at the memorial to his visits to the area, and get a few snaps.

Obvious to the military enthusiast is a trio of naval guns at the memorial, and an anchor atop the plinth. I snapped a few photos, intending to research the guns a bit better.

I have come up mostly empty-handed this far. All that I can figure out was that they do not appear to have been left there by Cook, but were placed there at a later date, if you can go by the historical photographs. This one from the 1920s or 30s:

I have been able to figure out that 2 of these are (probably) 12 or 24 pounder SBML (Smooth Bore Muzzle Loading) naval deck guns, sometimes used for shore emplacements. The current replacement carriages appear to be a bit makeshift, and they have no wedges for elevation.

The 3rd (and longer cannon) is seemingly devoid of markings, and seems to have been immersed in water for some time, and has damage to the muzzle. All three are cast iron cannons, which would date them to the 18th Century.

The 2 better preserved guns bear the Royal Cypher of George III, and are of the Armstrong design, rather than the later Blomefield. This places their date of manufacture somewhere in the last 5 decades of the 18th Century, or 1st decade of the 19th. This does fit with the time Cook explored the Pacific in his Endeavour and Resolution. Placing them at the memorial has proven historically accurate then.

Barrel Top Markings: The barrel has an embossed cypher: A crown above a stylised mark of a 3, G and R entwined. This indicates 'George Rex' and is the royal symbol of King George III who reigned from 1760 - 1820. Many of these and the later Blomefield design were used in the Napoleonic wars, and were standard English Navy issue guns.

George III had by the mid 1810s succumbed to mental illness (now though to be due to porphyria), and his son George, the Prince Regent had been granted Regency powers in 1811.

George III's long reign was marked by a series of military conflicts involving his kingdom and much of the rest of Europe. Early in his reign, Great Britain defeated France in the Seven Years' War, becoming the dominant European power in North America and India.

However, many of its American colonies were soon lost in the American Revolutionary War, which led to the establishment of the United States. Later, the kingdom became involved in a series of wars against revolutionary and Napoleonic France, which finally concluded in the defeat of Napoleon in 1815.

My photograph of one the southernmost gun at Ship Cove

Comparison gun cypher from a gun in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa (nicked off the net)

(Happy to credit photographer if requested)

Below the crest is a broad arrow signifying British government ownership of the weapon.

The design of the guns, specifically that of the knobs/butts or buttons lead me to believe they are therefore Armstrong or Armstrong-Frederick designs rather than Blomefield (See my reasoning below) . I did not have time to take photos of other distinguishing aspects such as manufacturers marks on the trunions, much to my frustration. I would love to learn more about the history of the Ship Cove cannon.

I have tracked down two similar guns, with a fascinating history of their own:

The Johnsonville guns (clicky)

These guns

(Johnsonville/Trentham) appear to be the of a different (and later) manufacture though.

The Ship Cove guns are missing the quoin or aiming/elevation wedge.

On the deck of a ship the gun would have been restrained with ropes to control the recoil

Armstrong and Blomefield:

In 1722, John Armstrong became the English Surveyor General of Ordnance. He was a man of immense energy who controlled the development of British ordnance over the next 20 years. He set about improving upon, and adding his own stamp to, the standard designs developed by Borgard.

By 1725 he had developed a complex series of proportions which governed the dimensions of every section of the cannon. Gone was the craftsmanship and decorations of the last century. What was left was a cast iron brute which could be cast to the same specifications by any foundry.

Armstrong (standing with the seated Duke of Marlborough)

Some minor modifications were made to the Armstrong pattern in 1753 under the guidance of Charles Frederick as Surveyor General, and thus creating the Armstrong-Frederick pattern gun. The Armstrong, or Armstrong-Frederick was finally supplanted in 1794 by the Blomefield pattern gun.

All in all, the Armstrong was a successful and resilient design and it was still present on British warships as late as 1808.

Armstrong's design for naval guns

Blomfield design - note the redesigned button with a loop

This gun is also mounted on a metal garisson type carriage vs the naval carriages above.

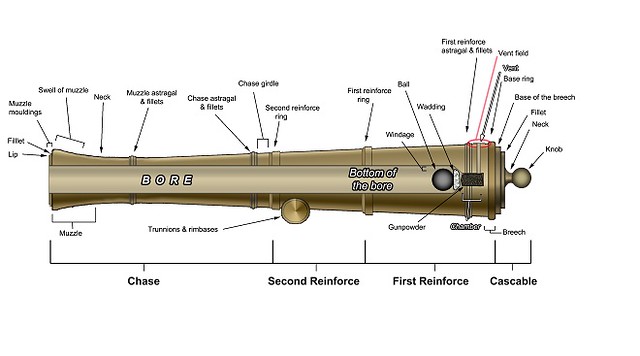

General anatomy and terminology of a SBML Naval Gun of the 18th Century:

Once John Armstrong had finished his basic design for British artillery in 1725, there were only marginal changes to the template over the next 70 years.

That changed In 1780, when a 36 year old artillery captain was appointed as Inspector of Artillery and Superintendent of the Royal Brass Foundry. Thomas Blomefield, was 11 years old when he was sent to sea on HMS Cambridge under a close friend of his father, Sir Peircy Brett. His naval career was short lived and in February 1758 he enrolled as a cadet at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich.

He was a talented student, gained the notice of his professors and passed out as a lieutenant eleven months later at age 15. He saw combat in the West Indies and Florida. He became aide de camp to General Conway, who was then acting Master General of the Ordnance and was retained in that position by his successor, Lord Townshend.

He resigned that high profile post to serve in the war in America. He was wounded in the head at Saratoga, returned to his duties as aide to the Master General of Ordnance. In 1780 he was appointed Inspector of Artillery and Superintendent of the Royal Brass Foundry.

At the time Britain’s military administration was virtually belly up. The nearly medieval system of military administration used by Britain was obviously incapable of supporting an army and navy engaged in a worldwide war.

Blomefield set about his task with energy. In his first year he condemned 496 new artillery pieces and unsuitable before they were sent to the army or the fleet. This represented about a quarter of the national production.

Around 1783, Blomefield set his hand to designing artillery. Apparently he was a dedicated experimenter and used his experiments to inform his designs. There are several key deviations from the Armstrong-Frederick pattern gun in the Blomefield gun.

First, it is much more simple in design. A lot of the more decorative features at the cascabel were done away with to ensure a uniform thickness of metal.

Second, an attempt was made to lessen the weight of the gun by trimming the thickness of the tube while retaining a strong breech. This is a theme one sees with cast iron guns probably culminating in the Parrot guns

Third, the chamber for the powder bag was a bit larger in diameter than the bore. This resulted in a better burn rate for the powder and hence a higher muzzle velocity.

Lastly, a loop was forged over the knob on the cascabel. Aboard ship, this enabled the breeching rope to pass through the loop rather than being looped around the knob. This subtle change enable shipboard artillery to be shifted much farther off the center line because it could be fired with the risk of snapping the breeching rope.

After 1794 the Blomefield pattern gun was the standard within the navy.

.jpg)

.jpg)